Indigenous Ways

An Indigenous Strategy: The ‘Right Thing to Do’

The development of an Indigenous Strategy is the ‘right thing to do’ for the University of Saskatchewan. We have constitutional/Treaty rights (e.g., Constitution Act 1982, UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), human rights (e.g., Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; Canadian Human Rights Act, 1977; Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982), moral and ethical obligations to ensure this work is “done in a good way”, and with integrity.

The Many Voices of Indigneous People

The Indigenous Strategy reflects the voices of Indigenous peoples from across Saskatchewan, specifically those who have a deep connection to the University and its history; primary language groups in Saskatchewan include Plains Cree, Woodland Cree, Swampy Cree, Dene, Dakota, Lakota, Nakota, Saulteaux, and Michif.

We have communicated key Indigenous principles and terms throughout this strategy in several Indigenous languages native to Saskatchewan as a sign of respect to the voices that created this strategy and to uphold our linguistic and cultural history. Each main section of the Strategy is introduced in six Indigenous languages—in order of appearance: Dene, Dakota, Nakota, Saulteaux, Michif and Plains Cree—in addition to English. Further, use of Indigenous terms in the body of the strategy is denoted with the Indigenous language group in parentheses.

Let Us Lead with Respect

DEVELOPING THE INDIGENOUS STRATEGY

The development of the Indigenous Strategy is rooted in the Indigenous principles of nīkānītān manācihitowinihk (Cree) and ni manachīhitoonaan (Michif )—which translates to “Let us lead with respect”. By leading with respect, we ensure that the Indigenous strategy reflects the voices of Indigenous peoples. Eight gatherings were held with Indigenous peoples over a seven-month period: a kēhtē-ayak (Elders) and Traditional Knowledge Keepers Gathering began our strategic process “in a good way”, convening the largest gathering in University history.

Indigenous Strategy Development Timeline

Engagement Advice and Guidance Meetings with Indigenous Communities

- April 17: Indigenous Strategy Proposal, Presentation to Senior Leaders Forum - Saskatoon Inn, Saskatoon

- November 1: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers - Holiday Inn Express, Saskatoon

- November 29: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous Community and Organizations - Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Saskatoon

Engagement Advice and Guidance Meetings with Indigenous Communities Continues

- January 30

- Morning: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous Undergraduate Students – Green Room, Administration Building, USask

- Afternoon: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous Graduate Students – Green Room, Administration Building, USask

- January 31

- Morning: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous staff– Green Room, Administration Building, USask

- Afternoon: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous faculty– Green Room, Administration Building, USask

- March 7: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers – Holiday Inn Express, Saskatoon

- April 2: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous undergraduate students – College of Education Building, USask

- April 4: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous undergraduate students – Health Sciences Building, USask

- April 5: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Indigenous undergraduate students – Arts and Science Building, USask

- May 30: Engagement, Advice and Guidance Meeting with Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers – Parktown Hotel, Saskatoon

- October: Indigenous Strategy Draft Development

Presentations of Draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous Peoples

- March 31: Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers cancelled due to COVID 19

- April 7: Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous Undergraduate and Graduate students – Zoom Meeting Room

- April 8: Planning and Priorities Committee

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous staff – Zoom Meeting Room

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous faculty – Zoom Meeting Room

- April 9:

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous faculty – Zoom Meeting Room

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous staff– Zoom Meeting Room

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous Undergraduate and Graduate students – Zoom Meeting Room

- Presentation of draft Indigenous Strategy and Validation Sessions with Indigenous Undergraduate and Graduate students – Zoom Meeting Room

- May 6: Meeting with Elders, Traditional Knowledge Keepers, Language Keepers – Naming, Advice/ Guidance on ceremonial aspects of strategy launch

- May 7: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan – Presidents Executive Committee

- May 12: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan Deans Council

- May 12: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan – Finance and Resources AVP/Directors

- May 13: Indigenous Strategy presentation to Presidents Executive Council – Council Chairs

- May 21: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan University Council

- May 25: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan Provosts Advisory Committee

- May 26: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan Teaching, Learning, and Academic Resources Committee of Council

- June 18: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan University Council

- June 19: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan Alumni Advisory Board

- July 7: Indigenous Strategy presentation to University of Saskatchewan Board of Governors

- October 18: University of Saskatchewan Senate (motion to accept gift)

Strategy Through Indigenous Perspectives

We gift this strategy to the University of Saskatchewan. Indigenous peoples from the city of misâsk- watômina (Saskatoon), the province of kisiskâciwan (Saskatchewan) and beyond; Indigenous students, staff, faculty, and leaders with a direct connection to the University; and kēhtē-ayak (Elders), oskâpêwak (Elder’s Helpers), Knowledge- and Language-Keepers who recognize the University’s role in building communities across this province have given voice to this strategy as an expression of self-determination, an invitation to reset relationships and gift a framework for the University of Saskatchewan’s reconciliation journey.

As a gift, this strategy is a symbol of reciprocity and requires acknowledgment of our responsibilities. For Indigenous peoples, this strategy embodies a spirit of belonging, empowerment and hope that change is possible.

For non-Indigenous peoples who have received and accepted this gift, this strategy should enlighten and guide. It creates the ethical space to imagine new models of scholarship, research, teaching and engagement that will uplift Indigenous ways of knowing and being for everyone, embolden a new kind of University of Saskatchewan student, and enrich the University’s role in building resilient communities across the province, Canada and the globe.

Written by and with Indigenous people, this strategy’s voice represents Indigenous languages, philosophies and spirituality. Four questions central to Indigenous ways of understanding our connections to place, time and community—and our role in honouring our ancestors and shaping our shared destiny—underpin the conceptual framework of this document:

- Who are we?

- Where do we come from?

- Where are we going?

- What are our responsibilities?

Our Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers gifted us with metaphors that captured the essence of this Indigenous strategy. We consulted with them first on the strategy and then learned teachings that embody the strategy. Teachings that can be lovingly and mindfully encased in a nayâhcikan – a parchment for safe keeping. These teachings are evident in our actions – actions that communicate one’s ethic of care for ‘all my relations’.

The name of the University of Saskatchewan Indigenous Strategy is ohpahotân | oohpaahotaan. This name symbolizes growth, journey and relational teachings that guide and strengthen our lives and work. ohpahotân | oohpaahotaan was drawn from ohpahowipîsim (flying up moon). During this moon, after a time of being nurtured in a nest and experiencing the world from the ground, a new generation of birds take flight. There is so much symbolism to the flying up moon for our First Nations, Métis and Inuit students – and for all people.

This moon can be representative of a rite of passage. In taking flight, there is the experience of pushing past a boundary into a whole new world – a whole new perspective. In taking flight for the first time, the once baby winged ones, see creation in a new way, and once this step is taken, they can never unsee this new space. Everything has just gotten more expansive, richer in colour and scope. There are new freedoms and opportunities to become more self-determined. Through ohpahotân| oohpaahotaan, the Indigenous Strategy, the University of Saskatchewan can continue to break boundaries and push past barriers that inhibit real and long-lasting respectful relationships, ones that inspire authentic collaborations that lead to system wide transformational change. ohpahotân| oohpaahotaan requires courage because its essence is dynamic discomfort that is required for revolutionary growth.

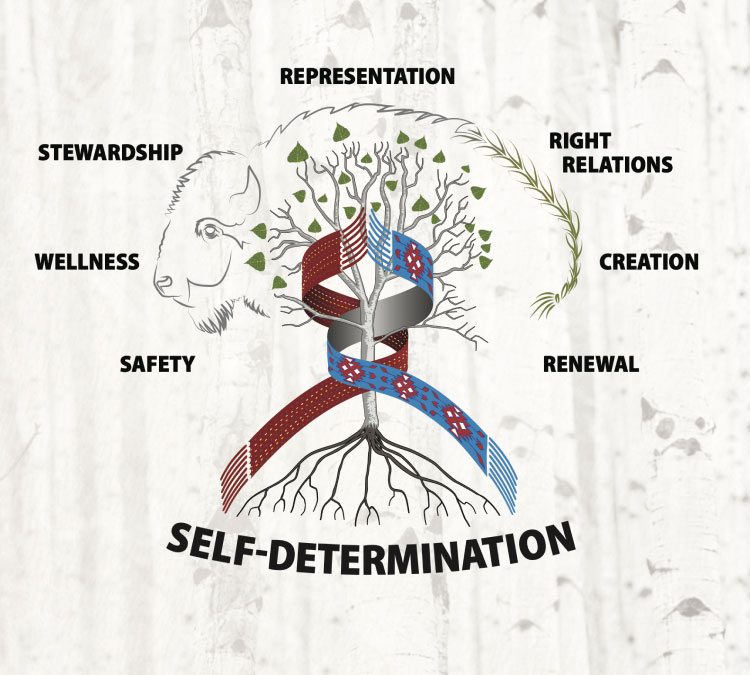

The metaphor of the double-helix emerged as a dynamic, resilient, continuous and non-linear process. Each strand is unbroken, and its path is not singular. Together, the strands can stretch or compress like a coil; they can rotate in clockwise motion around each other towards the future or be reset to include the past, never leaving anything behind—memories, histories, stories, knowledges, ancestors. And with these seemingly opposing forces, despite the constant and fluid evolution, the double helix remains whole, actively striving for equilibrium and the realization of its truth. The double helix is the visible and invisible expression of creativity— emerging and being sustained by the tangled and dynamic forces of flux, the relationship of chaos and order. A double helix helps us to imagine the connections across space and generations whose integrity is central to the wholeness of Indigenous self-determination. This metaphor helps to bring character, personality, life and spirit to the Indigenous Strategy. Within our Indigenous Strategy, much like the poplar tree and its genetic code, are the cherished life forces of Indigenous breath (voices, stories, histories, ways of knowing, being and doing) meant to transform the USask ‘in good ways’ for future generations. In its transformation, we honour the past and see the truth in the present.

The bison and sweetgrass offer other teachings. For example, they teach the importance of sacrifice, sanctified kindness, reciprocal respect and using our education for ourselves as well as the collective good of others.

A bison subtly yet powerfully frames the poplar canopy. As the image suggests, the bison holds a place of prominence for Indigenous peoples of these territories. The bison generously sustained the Indigenous peoples of the Plains for thousands of years. Their presence was abundant in North America (estimated to be approximately 50 million bison just 200 years ago), until they were nearly obliterated by newcomers. Blair Stonechild (Cree-Saulteaux) explains, “Today, elders say that education, rather than the bison needs to be relied upon for survival” (2006, pp. 1-2). This is a powerful statement for the role that education has today. Like the bison, education represents hope, security and sustainability for Indigenous youth today—it is a new means of survival—not as assimilation but in balancing knowledges and encouraging the resurgence of Indigenous peoples’ aspirations and self-determination.

The bison for the Indigenous Strategy represents fortitude, endurance, and the determination to survive and thrive in the midst of struggle, challenge, and forces that were designed to silence, overcome and annihilate. The bison survived brutal systematic onslaught; Indigenous peoples have survived genocide. Strength of spirit, audacious resiliency and resolve to be present and alive are parallels between these two relatives.

Bison fiercely protect their young, and they move in herds to ensure safety. This metaphor also symbolizes the collective responsibility that our whole campus community has to encouraging and guiding our students, and those that wish to enrich their knowledge and enhance their lives, at our University; it symbolizes the responsibility we have to create safe spaces and places that are conducive to thriving.

Gracefully and gradually, the top of the bison flows into a sweetgrass braid representing interconnectedness and inextricable relationships.

Within our homes, organizations and societies, it is important to recognize the importance of braiding/weaving together resources, actions, initiatives, programming and policies that support wholistic health, and promote values, belief systems that enhance and strengthen individual and collective identities. Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi) reminds us to be very present and mindful in the act of braiding. Before braiding sweetgrass she suggests: “Hold the bundle up to your nose. Find the fragrance... and you will understand...Breathe it in and you start to remember things you didn’t know you’d forgotten” (2013, p. ix). A braid is made tighter when two people work together, one holding firmly on one end while the other tugs and weaves the strands, both feeling the pressure of the creative energy. Inclusivity of a diversity of knowledges, cultures, and teachings from Indigenous peoples in our organization and transformations give rise to the needed tension in making our braid. We are required to do our part - to take an end of our strands, hold on tight, and provide the needed pressure and tension as we weave a tight sweetgrass braid.

If we have been successful, this strategy will awaken understanding, build relationships and inspire collaborative and respectful action driven by the spirit and intent of Treaty agreements—historic, current and future. We Are All Treaty People. If we have been successful, this strategy will coexist with the University Plan 2025 and allow us to walk parallel journeys toward a common future. If we have been successful, this gift will be received in the spirit intended by the Indigenous peoples who created and gifted it.

Indigenous Peoples

Our Four Teachers

This particular double helix, this DNA, this genetic code, has been in existence since time immemorial as the poplar tree. The poplar tree is sacred to Indigenous peoples of the prairies and beyond and over time they have honored the popular tree for its sustaining relationships. Its leaves, branches, trunk, bark, roots and sap have been used to nourish, heal, shelter and bring calm and warmth to the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged ones and those that crawl.

Once released by their ‘mothers’ and set in motion by the wind, poplar seeds can travel great distances and when settled, they grow tall quickly, always stretching towards the sun. Poplar trees thrive in many terrains, are skilled at quickly transforming barren landscapes with their fast-growing trunks, thriving in community (Wohlleben, 2015).

Our Connection to Land

While the conventional interpretation of the land is something that is immovable or inert, an Indigenous perspective of the term ‘land’ is something more.

Land is viewed in a more ‘wholistic’ sense as a living, breathing ecosystem and territory; a kin connection in an Indigenous worldview; and a place that we must learn from, nurture and sustain. For many of the kēhtē-ayak (Elders) engaged in developing this Strategy, Indigenous languages, protocols, stories, histories, and ways of knowing and being are intrinsically tied to the land. The land has always been our first teacher.

Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers Summit

Back row: Senator Sol Sanderson, Cy Standing, Sonia Starblanket, Wendell Starblanket, Rosalie Tsannie-Burseth, Eugene Arcand, Larry Oakes, Anthony Blair-Dreaver Johnston, Roland Duquette, (the late) Jacob Sanderson, Lorna Arcand, Louise Halfe, (the late) Frank Kayseas, Myrna Severight, Bob Badger, Enola Kayseas, Lyndon J. Linklater, Marie Battiste.

Front row: (the late) Jacob Pete, Leona Tootoosis, Margaret Keewatin, Maria Linklater, Monica Buffalo, Nora Cummings, Mona Creely-Johns.

Not pictured: Maria Campbell, May Henderson, Norman Fleury, Murray Hamilton, Edwin St. Pierre, Harriet Oakes-St. Pierre.

ëdƚąghįɁat’įɁa? / ountounwapi he? / dúwebi he? wenan neenawint? / awayna niiyaanaan? / awīna ōma kiyānaw? who are we?

Kisiskāciwan (Saskatchewan) comprises territory on four Treaty areas, and Saskatoon is on one of those, Treaty Six, whose First Nations Peoples entered into Treaty and laid the foundations for the provinces’ self-governance. Canada’s Constitution Act of 1982 recognizes and affirms our existing Aboriginal and Treaty rights, which comprise our Indigenous constitutions. The Constitution of Canada recognizes Indians (First Nations), Inuit, and Métis as the Indigenous Peoples of Canada.

As the original peoples of this land, represented as Turtle Island to some of us, we represent diverse knowledges, including a diversity of cultures, languages, traditions, and histories of our Indigenous ancestors, coming from many parts of the continent, and live as vibrant, distinctive, and sover- eign Nations and peoples through- out Canada. Our knowledges are distinctive to the unique ecosystems and territories in which we live, and we are thus deeply embedded in the fabric of the land and territories, its histories, and its development.

Our Nations across Canada continue to grow, with over 1.6 million people living in all of the provinces and territories across Canada. While the Constitution Act recognizes three distinctive groups, Indians (First Nations), Inuit, and Métis, it overlooks our inherent diversity; with over 700 Métis, First Nations and Inuit Nations across Canada, possessing a rich linguistic history that includes over 60 distinct Indig- enous languages within 12 linguistic families.

Indigenous peoples have lived on the land now known as Saskatchewan—in the tip of a vast maskotew (prairie ecosystem) that blends into ayapâskweyâw (a northern bush ecosystem)—since time immemorial. Indigenous peoples comprise more than 16% of Saskatchewan’s population (>175,000 people)1, having grown 22% since 2006 and rep- resenting over 70 Nations. We have a deep connection to the University of Saskatchewan. Indigenous peoples made important contributions early in the University’s history. As examples, Edward Ahenakew (Cree, from the Ahtahkakoop First Nation) was USask’s first Indigenous graduate in 1910; James McKay, the first Indigenous (Métis) judge appointed to the Saskatchewan court in 1914, served on the University’s first Board of Governors; Annie Maude “Nan” McKay, the first Métis student and Indigenous woman to graduate from USask in 1915, was one of USask’s earliest Indigenous hires and was instrumental in forming the alumni association; and, more recently, Dr. Karla Jessen Williamson (kalaaleq) became the first Inuk to be tenured at any Canadian University.

Over the past century, the University’s connections with Indigenous peoples, cultures, histories and traditions have vastly expanded and strengthened, helping to advance understanding of the history of Indigenous peoples and issues affecting all Canadians. Today, Indigenous peoples’ strong connections with the University of Saskatchewan and integral contributions to the University’s innovative Indigenous programming, research, scholarship, community engagement and governance are uplifting the experience of reconciliation and helping to deepen the University’s Indigenization, reconciliation and decolonization efforts.

Our relations with our families, our communities, our Nations, our cultures and our territories are fundamental to Indigenous ways of knowing and integral to Indigenous self-determination. Our connections transcend time and space; we have relations with and are responsible for the seven generations that came before us and the seven generations yet to come. Indigenous peoples appreciate that everyone and every- thing in the world has a purpose and is worthy of our respect and compassion. We have a responsibility to be stewards of all that is Mother Earth—to learn from the land and its ecosystems, to understand the nature of things, and to nurture and sustain the place that has given us our life and our livelihood.

ëdƚįniɁots’įɁait’įɁá? / tokitahan ounhipi he? dókiya ecídayabi he? / ahndi gaa ondosayang? taanday ooshchiiyaahk? / tāntē ōma ē ohtohtēyahk? where do we come from?

WE COME FROM CREATOR

We are original peoples, distinct peoples, as depicted through our stories of creation and life.

WE COME FROM TURTLE ISLAND AND ITS UNIQUE ECOSYSTEMS AND TERRITORIES

We have lived on Turtle Island since time immemorial. We built sophisticated settlements and nurtured thriving communities across this great land. As stewards of Mother Earth, we have a special relationship with this land and all the beings that live here—all have spirit.

WE COME FROM A LEGACY OF RESILIENCE AND SELF- DETERMINATION

We have stood strong in the face of injustice. Ever since the arrival of the “newcomer” some 500 years ago, Indigenous peoples have experienced unspeakably harsh realities. Our land was and continues to be colonized by settlers. Our communities were displaced. Our languages, cultures and belief systems were challenged.

WE COME FROM A PLACE THAT VALUES RELATIONSHIPS

With deep appreciation for the interconnectedness of all things, we recognize the value of maintaining right relations with our families, our communities and all peoples who inhabit Turtle Island and its unique ecosystems and territories. Throughout history, there are many examples of fruitful collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

WE COME FROM A PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE SHAPED BY HOPE

We have long hoped for peace and prosperity. Despite the challenges that our communities have faced, we continue to believe in the promise of a brighter tomorrow. Fulfilling this promise will require us to challenge deep rooted systems, structures, narratives and thinking to promote decolonization, reconciliation and Indigenization.

tokiya ounyanpi he? / udókina he? / ahndi eazang? taanday itoohtayaahk? / tāntē ōma ē itohtēyahk? where are we going?

A number of wise practices have been implemented over the years to realize USask’s commitment to Indigenous peoples through research, teaching and community engagement efforts, in particular those that highlight the importance of land- and place-based education. Many of these efforts have involved Indigenous community organizations, cultural centres, student bodies, staff and faculty—spearheading efforts or partnering on initiatives to advance Indigenization. It is important to identify and recognize these efforts and successes within our units, departments, colleges and the University as we look to the future. For instance:

- Through the work of Indigenous community and cultural centres, the creation of the Indian Teacher Education Program, the largest First Nations-specific program in Canada that has served over 16 First Nations communities/partners since 1974.

- Formation of the Indigenous Law Centre (formerly the Native Law Centre) to facilitate access to legal education and information for Indigenous peoples and promote the evolution of the Canadian legal system to better accommodate Indigenous peoples and communities.

- Establishment of the Rawlinson Centre for Aboriginal Business Students, one of the only such dedicated spaces for Aboriginal business students in the country.

- Development of Indigenous-led/focused research and education initiatives and programs.

- Concerted efforts to elevate the proportion of Indigenous students and faculty.

- Creation of committees to address topics of relevance to Indigenous students, staff, faculty and leaders (including racism and oppression).

This Indigenous Strategy is intended to unite with the University Plan 2025 and inspire meaningful and respectful action to advance Indigenization and support transformative decolonization leading to reconciliation. This strategy is a gift to the University that draws upon the wisdom, knowledge, cultures, traditions, histories, lived experiences and stories of Indigenous peoples.

Gordon Oakes Red Bear Student Center

Opened in January 2016 as an intercultural gathering place, the Gordon Oakes Red Bear Student Centre brings together the teachings, traditions and cultures of the peoples of kisiskâciwan (Saskatchewan). Grounded in the teachings of collaboration, cooperation, humility, reciprocity and sharing, the Centre aims to enhance First Nations, Métis, and Inuit student success.

Framework and Implementation

Learn more about the ohpahotân | oohpaahotaan framework and implementation.

We are all in this together.

Glossary and References

Glossary of Terms

Anti - racism is a study and theory about systems of power and how it is enacted, naturalized and invisible to those with power across classifications of race, class, gender expression and sexual identities, and abilities that diminish and subject groups to oppression. The awareness of power and contributing ideologies that hold power is what anti-racism helps to uncover for both the empowered elite groups and the disempowered or oppressed groups. It is needed for everyone to unlock, unpack and deconstruct those ideas, ideologies, and limitations on society.

Decolonization practices contest divisive and demeaning actions, policies, programming, and frameworks. Indigenization is the healing, balancing force; it calls us to action, inspires opportunities for mutual cultural understanding, and helps us to find comfort in the discomfort decolonization can entail.

Ethical spaces arise when competing worldviews or ‘disparate systems’ come together for ‘engagement’ purposes. The connecting space, the overlapping space between the groups is the binding ethical space. Cree Scholar Willie Ermine, notes that the convergence of these groups “can become a refuge of possibility in cross-cultural relations ... The new partnership model of the ethical space, in a cooperative spirit between Indigenous peoples and Western institutions, will create new currents of thoughts that flow in different directions and overrun the old ways of thinking” (Indigenous Law Journal, 2007, 6:202-203).

Indigenization challenges us to amplify the forces of decolonization. Indigenization strengthens the fabric of the University. It involves the respectful, meaningful, ethical weaving of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit knowledges, lived experiences, worldviews, and stories into teaching, learning, and research. Indigenization is a gift that benefits every member of our community.

Microaggression a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority) (e.g., You don’t look Indigenous.)

Reconciliation is a goal that may take generations to realize. It “is about forging and maintaining respectful relationships. There are no shortcuts” (Senator Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission). As a community, we have a shared responsibility to honour and join in the journey of reconciliation; to repair, redress and heal relationships; and nurture an ethical space in which we can explore how we relate to each other through the lenses of history, culture, and lived experience.

Settler colonialism is a term that is used to describe the history and ongoing processes/structures where- by one group of people (settlers) are brought in to replace an existing Indigenous population, usually as part of imperial projects. Settler colonialism can be distinguished from other forms of colonialism by the following characteristics:

- Settlers intend to permanently occupy, and assert their sovereignty, over Indigenous lands.

- This invasion is structural rather than a single event, designed to ensure the elimination of Indigenous populations and control of their lands through the imposition of a new governmental/legal system.

- The goal of settler colonialism is to eliminate colonial difference by eliminating Indigenous peoples, thereby establishing settler right to Indigenous lands. Though often assumed to be a historical process, settler colonialism as a project is always partial, unfinished, and in-progress. Examples include Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

“Wholistic” is a term that is used throughout this document and has been intentionally spelled with a “w” to represent the spiritual wholeness that defines Indigenous ways of being and gives life to this strategy.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/microaggression unwrittenhistories.com/imagining-a-better-future-an-introduction-to-teaching-and-learning-about-settler-colonialism-in-canada

References

- Anderson, K. (2011). Life Stages and Native Women: Memory, Teachings, and Story Medicine. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press.

- Association of Canadian Deans of Education. (2010). Accord on Indigenous Education. https://csse-scee.ca/acde/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/08/Accord-on-Indigenous- Education.pdf

- Coyle, M., & Borrows, J. (2017). The right relationship: reimagining the implementation of historical treaties . University of Toronto Press.

- Cajete, G. (Ed.). (1999). A people’s ecology: Explorations in Sustainable Living. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

- Cardinal, C & Hildebrant, W. (2000). Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan: Our Dream is that our Peoples will One Day be Clearly Recognized as Nations. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press.

- Christensen, D. (2000). Ahtahkakoop: The Epic Account of a Plains Cree Head Chief, His People, and their Struggle for Survival 1816-1896. Shell Lake, SK: Ahtahkakoop Publishing.

- Ermine, W. (2007). The Ethical Space of Engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193–204. TSpace.

- National Indian Brotherhood. (1973). Indian Control of Indian Education: Policy Paper Presented to the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Ottawa, ON: Assembly of First Nations. Retrieved on September 13, 2020 from https://oneca.com/ IndianControlofIndianEducation.pdf

- Kimmerer, R. (2015). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. The First Nations Principle of OCAP ®. http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) (1996). Final Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa, ON: Canada Communications Group.

- Stonechild, B. (2006). The New Buffalo: The Struggle for Aboriginal Post-Secondary Education in Canada. Winnipeg, MN: University of Manitoba Press.

- Government of Canada. (2018). TCPS 2 – Chapter 9: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter9- chapitre9.html

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg, MN: Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada. Retrieved on September 13, 2020 from http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/ Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- United Nations. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/ sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

- Wohlleben, P. (2015). The Hidden Life of Trees, What They Fell, How They Communicate: Discoveries from a Secret World. Vancouver, BC: Greystone Books.

Gifting the Strategy

ohpahotân | oohpaahotaan ("Let's Fly Up Together" ), The Indigenous Strategy was gifted in a ceremony on August 20, 2021 to the University of Saskatchewan on behalf of the Indigenous Peoples who informed and validated the process as a companion to the nīkānītān manācihitowinihk ni manachīhitoonaan (University Plan 2025).